Echoes of Big Tobacco: How Food Corporations Secure Power by Buying Legitimacy

- Dec 9, 2025

- 5 min read

For decades, powerful corporations producing potentially harmful commodities—from tobacco to ultra-processed foods and pharmaceuticals—have employed rigorous strategies to protect their profits and deflect criticisms regarding public health. Recently, the playbook has undergone a significant transformation: these industries are now actively positioning themselves as a necessary "part of the solution" to the very health problems their products exacerbate. This strategic repositioning, characterized by appeasement, co-option, and partnership, aims to secure regulatory capture and maintain corporate legitimacy in an increasingly hostile public and political environment. Understanding this shift is crucial for safeguarding public health policy globally.

.

The Old Playbook: Conflict and Denial

Historically, the food industry, much like the tobacco industry, deployed overt and confrontational tactics to protect business interests. These older strategies included three main dimensions:

Attacking Science and Planting Doubt: Corporations funded research to dispute evidence linking their products (such as sugary drinks) to diseases like obesity, deploying "fake scientists" and think tanks to deny or distort considerable bodies of scientific evidence.

Manipulating Policy Mechanisms: Tactics involved political donations, special interest pleading, and exercising influence through the "revolving door" (former federal employees becoming lobbyists) to block or undermine robust public health policies.

Fragmenting Opposition: Companies attempted to discredit researchers and public health professionals, even involving personal threats, monitoring, and surveillance. For instance, internal documents from Coca-Cola showed the explicit aim of campaigns was to “marginalize detractors”. This traditional playbook heavily emphasised personal responsibility as the cause of poor health, shifting blame from manufacturers and marketers to the individuals consuming the products.

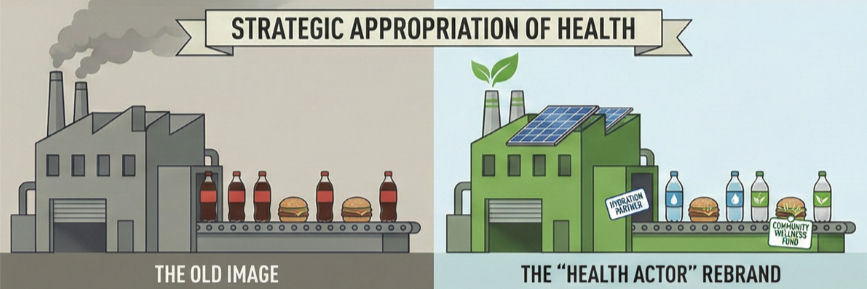

The New Strategy: Appeasement and Co-option

By the early 2000s, overwhelming scientific evidence of health harms and growing public awareness, combined with government bodies threatening legislation, compelled food corporations to reconfigure their approach. This resulted in the "part of the solution" strategy, built on three key pillars:

Regulatory Responses and Capture through Self-Regulation

Instead of simply opposing regulation, food corporations and trade associations now use self-regulation (voluntary pledges, commitments, or codes of practice) to diminish or pre-empt government regulation.

Pre-emption and Chill: Self-regulation initiatives, which can be modified and relaunched, are used to pacify public health pressure and pre-empt policy development, such as soft drink companies launching sugar reduction pledges when governments consider taxes or labelling laws.

Controlling the Narrative: This strategy reflects the industry’s attempt to demonstrate its capacity to participate in policy development consensually, arguing over who governs nutrition policy rather than what goes into it.

Imagine if big food commercials had to be honest

Relationship Building and Partnerships

Fostering relationships with government and health stakeholders has become a key method for bolstering corporate legitimacy.

Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs): Partnerships, often leveraging Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), are used to gain access to policy-makers and institutions, such as the public-private initiative Scaling Up Nutrition, which allows powerful companies to participate in World Health Organization (WHO) deliberations.

Co-opting Critics: These strategies can garner praise from outspoken critics, differentiating them from overtly oppositional political strategies. CSR initiatives and terms like “health branding” and “public health CSR” help corporations to reconstruct themselves as health actors, a process labelled the "strategic appropriation of health".

Funding Medical Bodies: This influence extends to medical associations. For example, the American Academy of Family Physicians accepted large sums from Coca-Cola to fund patient education on obesity prevention. The American Dietetic Association (ADA) has taken sponsorship money for fact sheets and incorporated industry-favorable positions, such as the idea that there are "no good foods or bad foods".

Market Strategies for “Healthier” Profits

Incremental Change, Maximum Profit: Nothing screams "we care about your health" quite like tweaking a recipe to cut a smidge of sugar or salt, or the "generous" acquisitions of organic and plant-based brands—Kellogg’s snatching up Morning Star Farms and PepsiCo swooping in on Health Warrior. Clearly, it’s all about boosting that bottom line while pretending to care about market share. Diffusing Pressure: These "innovative changes" are just a tiny step forward, addressing a few public health concerns while ensuring access to branded junk food. It’s a way to sidestep any real, radical changes that might actually make processed foods less available or affordable.

The Pervasive Threat of Conflict of Interest

This strategy of accommodation is a powerful and widespread form of influence that can be more enduring than coercive power. Nevertheless, it generates significant conflicts of interest, especially within government advisory bodies.

Compromised Guidelines: Key public health tools are vulnerable to corporate influence. For instance, a recent report found that almost half of the members of the US Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee (DAGC) had significant ties to major food, agriculture, and pharmaceutical companies like Nestlé, Pfizer, and Coca-Cola. Such findings “erode confidence in dietary guidelines” which are considered the "gold standard" globally and influence school and hospital food programs.

The "Funding Effect" in Nutrition Science: Much like pharma, the highly profitable food industry influences research outcomes by outspending independent sources. There is a well-documented "funding effect" where industry-sponsored studies are significantly more likely to conclude that a sponsor’s product is healthy or harmless compared to independent research. Key tactics include "cherry-picking" favourable trial results for publication and deploying paid opinion leaders—from respected academics to social media influencers—to defend controversial ingredients or promote processed foods as part of a "balanced diet."

Amplifying Uncertainty: The Role of Algorithms on Social Media

In the digital age, corporate-linked efforts to instill doubt or promote alternative narratives benefit from the structure of social media. Social media algorithms are designed to maximise engagement, meaning controversial and emotionally charged content—including conspiracy theories—often receives significantly higher engagement than factual, nuanced information.

The Rabbit Hole: Algorithms create "filter bubbles" and the "rabbit hole effect," leading users from mild scepticism (e.g., questioning pharmaceutical profits) to increasingly extreme narratives, such as anti-vaccine theories or beliefs that "Big Pharma" is concealing cancer cures.

The Power of Narrative: Conspiracy theories gain traction by offering simple, seemingly coherent explanations for complex events and fulfilling the human need for certainty and control, especially when trust in institutions is low.

A word from the authors

We must prioritize public interests over corporate desires. While partnerships may seem beneficial, they can normalize corporate influence in our food and health systems, enabling companies to advance their agendas with little resistance. To avoid past mistakes like those with Big Tobacco, we need clear regulations, unbiased evaluations free from industry funding, and vigilance against corporate tactics that mask profit motives. Steve & Jenny

References

Brownell, K. D., & Warner, K. E. (2009). The Perils of Ignoring History: Big Tobacco Played Dirty and Millions Died. How Similar Is Big Food? The Milbank Quarterly, 87(1), 259–294.,

International Food and Beverage Alliance. (2020). Our commitments: New and improved products + smaller portions.

Jelinek, G. A., & Neate, S. L. (2009). The influence of the pharmaceutical industry in medicine. Journal of Law and Medicine, 17(2), 216–223.,,,,

Lacy-Nichols, J., & Williams, O. (2021). "Part of the Solution": Food Corporation Strategies for Regulatory Capture and Legitimacy. International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 10(12), 845–856.,,,,,,,,,,,,,,

Mitchell, S. (2025). How Social Media Algorithms Amplify Conspiracy Theories. Merri Mortar Blog.,,

NutritionFacts.org. (Video Transcript). The Role of Corporate Influence in the Obesity Epidemic. (Source of the American Academy of Family Physicians funding by Coca-Cola detail).

Perkins, T. (2023). US nutrition panel’s ties to top food giants revealed in new report. The Guardian.,,,

Reuters. (2016). PepsiCo sets global target for sugar reduction.

Wikipedia contributors. (Accessed [Current Date]). Big Pharma conspiracy theories. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia.,,

Comments